Youngsters between hobby and peak performance - Measuring heart rate to explore the intensity of Carnivalistic Soloist Dance.

So-called “Carnivalistic” Dance” is for many not only a hobby but also a tough, competitive sport. Besides its cardio-vascular load, it demands peak performance in dancing and gymnastics. This thesis examined the heart rate behavior of female soloist dancers and aims to help athletes and their coaches who want to improve performance.

Why this project?

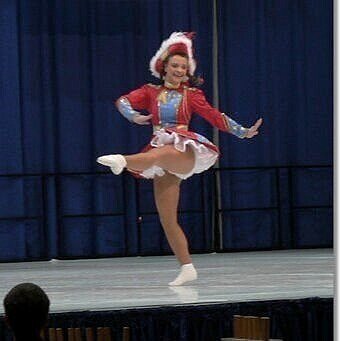

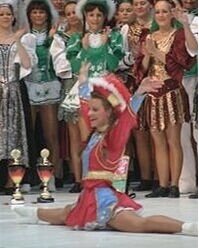

The idea for this thesis stems from my own experiences in this kind of sport. For more than a decade I have participated in competitions, with the German Champion title (2006) being one of my biggest achievements. This in return allowed my mum, sister and me to teach and lead others in the fields of Sport Science, choreographies, and gymnastics thanks to the attention that followed my athletic success. Within the many years of freelance work that followed, among others, we have been part of the official coach-license-education-team of BDK (Bund Deutscher Karneval e.V.). Additionally, we developed a training concept for acrobatics in Carnivalistic Dancing, which was published by my sister in 2008, and which we promoted through self-organized workshops all over Germany. During this time we had the chance to talk to thousands of athletes and coaches and could see the massive knowledge gap regarding training methods and performance development. But first and foremost we realized how threatening many training practices were for the often very young athletes' health. With this in mind, I wanted to raise awareness and provide a starting point for people to do more research in this area. I knew from my own athletic journey how demanding this kind of sport was and thought about opportunities to tackle it. That's how this project was born.

What is Carnivalistic Dance?

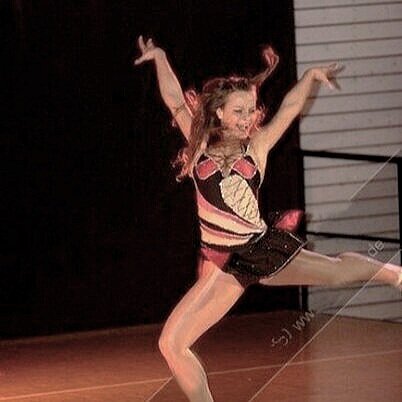

Carnivalistic Dance belongs to the technical-compositional, acyclic sport disciplines. It can be performed in a group, as a duo or as a soloist and contains complex, coordinative movements integrated into compositions accompanied by specific music (often military marches or instrumentals from folk music or soundtracks that follow common-time). Its characteristics derive from traditional global dance styles as well as gymnastics, resulting in a continuous - sometimes dogged - faster, higher, stronger mindset. Carnival and Carnivalistic Dance follows long traditions rooted in history. Members of the association (BDK) are requested to cultivate and keep alive these traditions within their activities and athletic compositions. This is first and foremost true for the concept of vitality. Carnival was originally supposed to drive out bad spirits through joy and humour (provide hope). Being happy, celebrating and socializing are most important to live the tradition. However, while these criteria are some kind of foundational guidelines, there has been a fundamental shift in the attitude taken place within the past decade towards performance optimization. Media and political interest followed and athletes developed more and more towards self-discipline, competitive thinking and a will to perform like a professional athlete. Choreographies became more spectacular, especially when it comes to gymnastics. Aerials, backflips, back-handsprings or twist - all performed on hard ground without supportive mats - have been part of the standard repertoire of the actual “dancers”. One can believe that taking part in such a demanding sport that requires strength, flexibility, coordination, agility, and endurance at the same time, would provide its athletes with proper, thought-through training concepts. But, due to its traditional nature, where the event "Carnival" instead of sports competition was in focus for several decades, these concepts are nonexistent. So, even though we are talking about a niche discipline, a basic scientific evaluation was desired to protect the often very young athletes from injuries, sickness and overtraining. As studies were lacking, we decided to run a simple pre-study to showcase the problem with physiological measures. For the sake of health but also to make the performance-evaluation-process fairer, we aimed to show instructors and the management board of BDK of the load we expect our athletes to shuffle. ‘

What did we do and how did the results look like?

This project was ultimately rolled out in the context of my Bachelor's Thesis, to explore heart rate behavior in Carnivalistic Soloist Dance. We conducted a heart rate measurement (Polar) to investigate intensity zones with 12 female, juvenile soloists aged between 10 and 16 years, who had a proficiency level in the range of 430 and 480 points (maximum 500 points; national top-level). The minimum precondition for participation was the ability to perform different dance-specific elements of floor and balance beam exercises. All participants were at the time of study in a four-week break of practice (post-season). There was at most a preservative gymnastic exercise once or twice a week. The own composition (including stage entrance) of the departed season was performed on a 25x15 meters sized floor (gymnasium) without the usual competition uniform. Heart rate was measured at a five-minute time interval prior to the dancing start as well as at the stage-entrance and during composition. In addition, heart rate information was recorded for a 3-minute time interval of regeneration after the athlete reached her ending pose. For analysis purposes, probands stacked time markers with their pulse watches at the start of the stage entrance, after being in starting pose and after being in ending pose.

The Maximum Heart Rate (HRmax) during the entire period of measurement was 194.4 beats per minute (bpm) on average, whereas the total Average Heart Rate (HRavg) showed a value of 143.5bpm. The heart rates at certain time markers revealed alternating values. Marker 1 (prior stage entrance) was measured with a HRavg of 138.9 bpm, while marker 2 (starting pose) showed an increase in HRavg with 168 bpm. Ultimately, marker 3 (end pose) was measured with the highest HRavg of 190.7 bpm. The Heart Rate Recovery (HRR) revealed furthermore very individual values ranging from 38-78 bpm relating to a 3-minute post-performance interval.

SO WHAT?

To interpret the results, we used established heart rate calculations. Because the study considered only female participants, formulas 220 – age, 207 – 0,7 x age and 226 – age were applied to receive better accuracy (gender/age dependency of HRmax). Overall, results have shown sub-maximal as well as mainly maximal cardio-vascular efforts. Therefore we can say that we often underestimate the actual load on athletes and ask physically but also mentally too much of them (e.g. “Don’t complain, dance again”). We deal with a high-intensity performance going along with central fatigue processes which we have to consider in our practice as coaches, judges, and parents. This also appeals to an athlete's responsibility to learn about exercise physiology as well as to say stop when needed. It requires parents to screen coaches and clubs better for methodological quality and it requires coaches as well as judges to update their knowledge and comparison criteria. However, the results of this pre-study should be examined critically. Even though we could give a rough overview of the cardio-vascular load in Carnivalistic Soloist Dance, we were facing many confounding variables including variations in fitness levels, training methods, and proficiency levels. Furthermore, speed and length of the chosen music track, as well as the absence of the uniform (additional weight and resistance), will most likely influence the overall performance load. However, due to poor standardization opportunities, we could at the same time identify weaknesses within the evaluation process and exemplify potential changes to BDK regulations (so-called "Tanzturnierordnung"). These changes include the combination and restructuring of evaluation categories, the addition of an endurance/intensity component as well as the introduction of music-lenght and -speed limitations to control for intensity.

Ultimately it can be stated that - with regards to physiological indicators - Carnivalistic Soloist Dance should be seen and named as a high-intensity "performance sport" rather than a "hobby" only. This study was conducted at the Department of Applied Sport Science of Technical University of Munich (TUM).

@KarnevalDeutschlandBDK

LITERATURE

Appell, H. J.; Stang-Voss, C. (2008): Funktionelle Anatomie: Grundlagen sportlicher Leistung und Bewegung. Heidelberg: Springer Medizin Verlag.

Bailey, R. C.; Olson, J.; Pepper, S. L.; Porszasz, J.; Barstow, T.J., Cooper, D. M. (1995): The level and tempo of children’s physical activities: an observational study. In: Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise (7), 1033-1041.

Baldari, C.; Guidetti, L. (2001): VO2max, ventilatory and anaerobic thresholds in rhythmic gymnasts and young female dancers. In: The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 41 (2), S. 177–182.’

Böhmer, D. (1988): Sportmedizinische Befunde bei Tanzsportlerinnen. In: Medau, H.J.; Nowacki, P.E. (1988): Frau und Sport III. Die Bedeutung der nichtolympischen Disziplinen für die sportreibende Frau. Beiträge zur Sportmedizin (33), S. 144-150. Erlangen: Perimed Verlag.

Cohen, J. L.; Segal, K. R.; Witriol, I.; McArdle, W. D. (1982): Cardio-respiratory responses to ballet exercise and the maximal oxygen intake of elite ballet dancers. In: Medicine & Science in Sport & Exercise14(3): S.212-217.

Davidson, D. M.: Dance and cardiorespiratory fitness. In: Shell, G.C. (1986), The dancer as athlete. Champaign: Human Kinetics Publishers. S.133-137.

Frische, Maja; Maassen, N. (2004): Die Wirkung eines hochintensiven, intervallartigen Trainings auf die Leistungsfähigkeit bei Sprint-Dauerbelastung und auf die Regenerationsfähigkeit. www.bisp.de/nn_1662194/SharedDocs/Downloads/Publikationen/Jahrbuch/Jb_2004_Artike l/Frische_Maassen,templated=raw,property=publicationFile.pdf/Frische_Maassen.pdf

Fröhner, G. (1992): Grenzen und Möglichkeiten der Belastung des Stütz- und Bewegungssystems am Beispiel junger Turnerinnen. In: Medau, H. J.; Nowacki, P. E. (1992): Frau und Sport IV. Die olympischen Disziplinen der Frau im Sport. Erstes gesamtdeutsches Sportmedizinisches Symposium in Coburg 1990. Beiträge zur Sportmedizin (41), S. 253-257. Erlangen: Perimed-spitt

Gellish, R. L.; Goslin, B. R.; Olson, R. E.; McDonald, A.; Russi, G. D.; Moudgil, V. K. (2007): Longitudinal modeling of the relationship between age and maximal heart rate. In: Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 39 (5), S.821.

Hohmann, A.; Lames, M.; Letzelter, M. (2010): Einführung in die Trainingswissenschaft (5., unveränderte Aufl.). Wiebelsheim: Limpert.

Hollmann, W., Strüder, H. K.; Predel, H.-G.; Tagarakis, C.V.M. (2006): Spiroergometrie. Kardiopulmonale Leistungsdiagnostik des Gesunden und Kranken. Stutgart, NewYork: Schattauer Verlag.

Hollmann, W.; Strüder, H. K. (2009): Sportmedizin. Grundlagen für körperliche Aktivität, Training und Präventivmedizin (5., völlig neu bearb. und erw. Aufl.). Stuttgart, New York: Schattauer.

Hottenrott, K.; Reinhardt, C.; Schwesig, R. (2007): Verhalten von Geschwindigkeit und Laktat bei Laufbelastungen im Herzfrequenz-Steady-State. In: Deutsche Zeitschrift für Sportmedizin 58 (7-8), S.235.

Isphording, R. (2011): Geschichtliche Entwicklungen im Karnevalistischen Tanzsport. Private Datensammlung und -aufzeichnung.

Israel, S. (1982): Sport und Herzschlagfrequenz. Sportmedizinische Schriftenreihe 21. Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth.

Janssen, P. G. J. M. (2003): Ausdauertraining. Trainingssteuerung über die Herzfrequenz- und Milchsäurebestimmung (3., überarb. und erw. Aufl.) Balingen: Spitta.

Kornexl, E. (1993): Nachbelastungsherzfrequenz als Leistungsindikator. In: Kornexl, E.; Nachbauer, W. (Hrsg.), Bewegung, Sport, Forschung. Innsbruck: Institut für Sportwissenschaften der Universität Innsbruck. S. 181-262.

Koutedakis, Y.; Jamurtas, A. (2004): The Dancer as a Performing Athlete. Physiological Consederations. In Sports Med 2004; 34 (10): S. 651-661.

Kozak, G. (2005): Karnevalistischer Tanzsport. Training, Methodik, Gestaltung. Bonn: Tanz-undMedien-Verlag.

Lehmann, M.; Keul, J.; da Prada, M.; Kindermann, W. (1980): Plasmakatecholamine, Glukose, Lactat und Sauerstoffaufnahmefähigkeit von Kindern bei aeroben und anaeroben Belastungen. Deutsche Z. für Sportmed. 31, S.230-236.

Löllgen, H.; Erdmann, E. (2009): Ergometrie. Belastungsuntersuchungen in Klinik und Praxis (3. Aufl.) Berlin: Springer Berlin.

Marées, H. de; Heck, H. (2006): Sportphysiologie (9. vollst. überarb. und erw. Aufl.). Köln: Sportverlag Strauß.

Neumann, G.; Berbalk, A.; Pfützner, A. (2011): Optimiertes Ausdauertraining (6., überarb. Aufl.). Aachen: Meyer & Meyer.

Nowek, O. B. (2004): Gardetanzsport I (1. Aufl.). Norderstedt: Books on Demand.

Schandry, R. (1998): Lehrbuch der Psychophysiologie. Körperliche Indikatoren psychischen Geschehens (Studienausgabe). Weinheim: Beltz, Psychologie Verlags Union.

Shephard, R. J.; Rost, G. (1993): Ausdauer im Sport. Eine Veröffentlichung des IOC in Zusammenarbeit mit der FIMS (Dt. Lizenzausg.). Köln: Dt. Ärzte-Verlag.

Simmel, L. (2009): Tanzmedizin in der Praxis. Anatomie, Prävention, Trainingstipps (1. Aufl.). Leipzig: Henschel.

Singh, T. P.; Rhodes, J.; Gauvreau, K. (2008): Determinants of heart rate recovery following exercise in children. In: Medicine and Science in Sports Exercise 40 (4), S. 601–605.

Stemper, T.; Kozak, G. (2005):Herzkreislauf- und Stoffwechselbelastung im Gardetanzsport. Symposium der dvs-Sektion Trainingswissenschaft vom 7.- 9. April 2005 in Bochum. In: Trainingswissenschaft im Freizeitsport: Deutsche Vereinigung für Sportwissenschaft / Sektion Trainingswissenschaft, S. 214–216.

Such, U.; Meyer, T. (2010): Die maximale Herzfrequenz. In: Deutsche Zeitschrift für Sportmedizin 61 (12), S.310-311.

Tanaka, H.; Monahan, K. D.; Seals, D. R. (2001): Age-predicted maximal heart rate revisited. Journal of the American College of Cardiology (37): S.153-156.